Abraham Lincoln Is the Only President Ever to Have a Patent

In 1849, a future president patented an amazing addition to transportation technology

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/0e/e20ef9e5-772d-4313-b351-f1d67913026d/nmah-2009-5611.jpg)

Upon hearing the name Abraham Lincoln, many images may come to mind: rail-splitter, country lawyer, young congressman, embattled president, Great Emancipator, assassin's victim, even the colossal face carved into Mount Rushmore. One aspect of this multidimensional man that probably doesn't occur to anyone other than avid readers of Lincoln biographies (and Smithsonian) is that of inventor. Yet before he became the 16th president of the United States, Lincoln, who had a long fascination with how things worked, invented a flotation system for lifting riverboats stuck on sandbars.

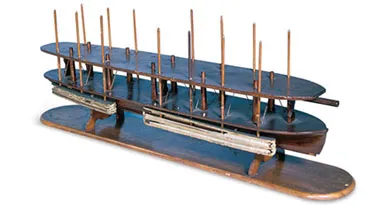

Though his invention was never manufactured, it serves to give Lincoln yet another honor: he remains the only U.S. president to have a patent in his name. According to Paul Johnston, curator of maritime history at the National Museum of American History (NMAH), Lincoln's eminence and the historical rarity of his patent make the wooden model he submitted to the Patent Office "one of the half dozen or so most valuable things in our collection."

Lincoln's patent, No. 6,469, was granted on May 22, 1849, for a device for "Buoying Vessels Over Shoals," when he was back in Springfield practicing law after one term as an Illinois congressman in Washington. His idea, to equip boats with inflatable bellows of "india-rubber cloth, or other suitable water-proof fabric" levered alongside the hull, came as a result of river and lake expeditions he made as a young man, ferrying people and produce on the Mississippi and the Great Lakes. At least twice his boats ran aground on sandbars or hung up on other obstacles; given the Big River's ever-shifting shallows, such potentially dangerous misadventures happened often. Freeing a beached vessel usually involved the laborious unloading of cargo until the boat rode high enough to clear the snag. According to Harry R. Rubenstein, chair of the Division of Politics and Reform at NMAH, Lincoln "was keenly interested in water transportation and canal building, and enthusiastically promoted both when he served in the Illinois legislature." He was also an admirer of patent law, famously declaring that it "added the fuel of interest to the fire of genius."

Lincoln appears to have had more than a passing affinity for mechanical devices and tools. William H. Herndon, his law partner at the time he was working on his invention, wrote that Lincoln "evinced a decided bent toward machinery or mechanical appliances, a trait he doubtless inherited from his father who was himself something of a mechanic...."

The precise source of the model of the flotation device is unclear, though there's no doubt that the ingenuity behind it was Lincoln's. Herndon wrote about Lincoln bringing the wooden boat model into the law office, "and while whittling on it would descant on its merits and the revolution it was destined to work in steamboat navigation." A Springfield mechanic, Walter Davis, was said to have helped with the model, which was just over two feet long. But Johnston thinks it's possible that the detailed miniature Lincoln submitted may have been made by a model maker in Washington who specialized in aiding inventors. "The name engraved on top of the piece is 'Abram Lincoln,'" Johnston says. "It doesn't seem likely that if Lincoln had actually made this model, he'd have misspelled his own first name." Johnston says that the answer—yet undetermined—may lie in whether the misspelled name is also engraved under the original varnish, indicating the model to be a commission.

The patent application for the device has a similar mystery. Part of the U.S. Patent Office collection, the document describes in detail how "by turning the main shaft or shafts in one direction, the buoyant chambers will be forced downwards into the water and at the same time expanded and filled with air." But it is missing the inventor's signature. Someone, probably in the early 20th century, cut Abe's signature out of the document—the autograph collector as vandal.

Since no one ever tried to put the invention to use, we can't know for sure if it would have led to the revolution in steamboat navigation that Lincoln predicted. But "it likely would not have been practical," says Johnston, "because you need a lot of force to get the buoyant chambers even two feet down into the water. My gut feeling is that it might have been made to work, but Lincoln's considerable talents lay elsewhere."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)